Wild Stories is a monthly essay in which I write about an animal, a plant, a landscape, or a natural phenomenon. With Wild Stories, I aim to foster a curiosity and a desire to learn more about the lives of our flora and fauna, as well as the remarkable and complex landscapes we inhabit.

I have studied nature for decades through observation, physical experience, and books. We share the planet with an abundance of species who inspire awe, wonder, joy, respect, and occasionally fear. For most of human existence, we have maintained a kinship and reverence for our co-species.

The Columbia River Gorge is one of the most “gorge-ous” (pun fully intended) canyons in North America, thanks to the protection provided by a federal national scenic area designation in 1986. That protection has ensured the natural beauty of the gorge is preserved: there are no McMansions, no industrial developments, and no subdivisions. The Gorge is a recreational playground of publicly owned lands, offering hikers, campers, mountain bikers, boaters, windsurfers, wildflower enthusiasts, hunters, and fishers, as well as millions of annual tourists, many opportunities to experience this unique landscape. (My plug for public lands.)

The Columbia River, which helped carve the canyon, serves as both a geographical and political boundary between the states of Oregon and Washington. If you travel the roughly 80 miles of the Gorge, you will witness several distinctive ecoregions that are influenced by the varied climates of the Pacific Northwest. In the west end, rain-soaked temperate conifer forests gradually give way to arid grasslands on the east end; the Gorge also offers extremes in elevation, ranging from river level to the peaks of the snow-capped volcanic mountains, Mount Adams and Mount Hood.

This diverse terrain features hundreds of plant species, several of which are endemic. Wildflower chasers like me can find blooms from February to September. I know several dedicated plant lovers who hunt wildflower blooms almost every week of the year, traveling the many recreational trails and Forest Service roads in the Gorge.

In her 2013 book Braiding Sweetgrass, author and biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer was asked by her freshman college advisor why she wanted to major in botany. She told him, “Because I wanted to learn about why asters and goldenrod looked so beautiful together.” Perennial wildflowers that bloom in the late summer, aster flowers are purple, and goldenrod flowers are yellow. She was curious: “Why do they stand beside each other when they could grow alone? Why this particular pair? What is the source of this pattern? Why is the world so beautiful?” Her advisor’s message was, “that science was not about beauty, not about the embrace between plants and humans.”

Don’t tell wildflower enthusiasts it’s not about beauty. One of the most popular places to visit in May is The Dalles Mountain Ranch, located in the eastern grasslands of the Gorge. People travel here not for its diversity of wildflowers but to witness the stunning display of purple lupine and yellow balsamroot. A former cattle ranch, visitors walk the short trails, many taking photo after photo of this display of two plant companions in bloom, as if seeking to make visual sense of this simple landscape.

Years later, Kimmerer learns that our ability to recognize color is because of three types of specialized receptor cells in our retina, one of which “optimally perceives light of two colors: purple and yellow.” When we see these colors together, signals are sent to the brain. She further explains that purple and yellow are complementary colors on the color wheel and noted that when paired, they “make each more vivid.”

Lupine

A common wildflower of the Pacific Northwest, lupines serve multiple ecological functions: they offer protein-rich food for a variety of animals, and as a legume, lupines are nitrogen fixers, improving the health of the soil. There are over 200 species of lupine, found primarily in North and South America, that inhabit a variety of terrains, including high deserts, meadows, forests, mountains, and sage steppe. This explains the diversity of sizes among species, as they have adapted to their differing landscapes. They grow easily and quickly, and can even become weed-like in their reproductive abilities.

Why Wolf Flower?

The plant's genus name Lupinus is based on the Latin lupus, which means "wolf-like," and there are several possible reasons offered for the wolf reference. One claims that the plant was often noticed growing in colonies with no other plants nearby, thus "wolfing" or robbing the soil of its nutrients. Another reason suggests that the plant's toxic seeds can kill livestock just like the wolf does. The more likely possibility is the connection to the Greek word lopos, which means 'husk' and refers to the dry outer covering of the seed pod. (In a future life, I would love to be an etymologist specializing in the origin and historical development of plant names.)

The Pea Flower Structure

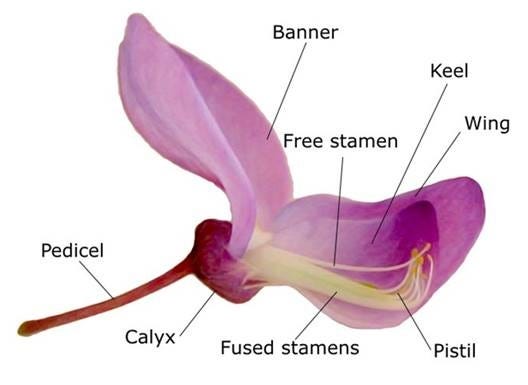

The differing sizes of species vary from small to shrub-sized, but they all present the classic 5-petaled pea flower: the larger two upper petals are called the banner, the two side petals are called wings, and the lower petal is called the keel. The stamens and style are hidden in the keel, and when their preferred pollinators, bumblebees, land on the keel, the stamens and style spring up, brushing the bee's abdomen with pollen. Lupine flowers are usually various hues of blue and white, and a few species are bi-colored.

The Lonely Lupine of Mount St. Helens

After Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980, research ecologists monitored the slow recovery of flora and fauna in the ash-laden blast zone, which was once an alpine forest and is now known as the Pumice Plain. A lone Prairie Lupine was one of the first plants to appear on the barren landscape that offered few nutrients to support plant life. Ecologists determined that the lupine's ability to fix nitrogen from the air allowed the plant to survive the harsh conditions and create its own microhabitat. The plant served as a trap for windblown organic debris and insects, which gradually contributed to the accumulation of organic matter in the surrounding soil. Over several years, that lone lupine plant turned into a thriving colony of lupine plants, nurturing an environment that supported an expanding diversity of plants and animals.

Is it Edible?

Many lupine species contain toxic alkaloids and are considered poisonous for human and livestock consumption. Lupine has a history as an edible seed, provided the bitter alkaloids are removed by soaking in running water. The seeds are being reintroduced as a native food for several South American indigenous groups. Lupini is a pickled snack food made with lupin seeds, served in Mediterranean countries and in South American countries that were colonized by these regions. Several PNW indigenous groups utilize lupine leaves as a source of edible food and for ceremonial purposes, while the roots are used to make cordage. One group used the lupine's flowering as a season indicator; the blooms indicated the groundhogs were fat enough to eat.

Balsamroot

Serving as little pockets of sunshine in May, a moody month of weather extremes in the Gorge, the bright blooms can be seen for miles as a blur of golden yellow as I drive up to the ranch.

A member of the sunflower family, balsamroot (Balsamorhiza spp.) is found throughout western North America. It is commonly associated with sagebrush communities, but can also be found growing in mountain shrub, pinyon-juniper, ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, and aspen plant communities. It is a robust soul: drought-tolerant, winter-hardy, grazing-tolerant, and fire-resistant, relying on its long tap root to grow new leaves and flowers after being exposed to fire.

Ecological Relationships

A wide variety of wildlife, including pollinators, utilize balsamroot. Deer, elk, bighorn sheep, and pronghorn eat the leaves, stems, and flowers. Balsamroot can be used to improve spring and summer forage in open rangelands for cattle and domestic sheep. Birds and rodents eat the seeds. As perennials that return early in spring, their presence helps keep melting snow from following gravity’s demand to run downhill.

Indigenous cultures utilize balsamroot as both a primary food source and a medicinal plant. Lewis and Clark observed Native Americans harvesting seeds to make flour, eating raw stems, and digging their large taproot (5-9 feet long) to roast or steam. The antifungal and antimicrobial properties of the leaves can be utilized as poultices, infusions, and salves to aid in wound healing. The woody, resin-filled taproot can be dug up (an arduous task) and used to make tea and tinctures for respiratory complaints.

RESOURCES: Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast; Sagebrush Country: A Wildflower Sanctuary; Mountain Plants of the Pacific Northwest; Pacific Northwest Medicinal Plants; Native American Ethnobotany

Thank you for being here. All of my posts are free, but if you’d like to support my work, you can do so by:

Liking and restacking this post so others are encouraged to read it.

Share this post via email or on social media.

Taking out a paid subscription to this Substack.

Check out my About page to learn more about me, my writing, and subscriber benefits. I maintain a linked index of my Substack articles here.

Comments are always appreciated.

How wonderful to read your Wild Stories, Sue! And as Janisse said below, I appreciate the reminder of Robin Wall Kimmerer's writing on yellow & purple, and the beauty they create. Why is it so hard for us to honor the importance of beauty and of loving this world?

Lupines and other pea/bean family plants who transform atmospheric nitrogen into a form that plants can use do that via a partnership with bacteria who live in nodules in the legumes' roots. The microbes do the chemical transformation of the nitrogen; the legumes feed and shelter the bacteria. It's a win-win for both organisms.

Beautiful. Arrow Leaved Balsamroot was a harbinger of spring for us when we lived in British Columbia.